Should you try Intermittent Fasting?

Trigger warning – the following post has blatant diet and calorie talk as it explores Intermittent Fasting, a kind of dietary intervention. If you or someone you know if struggling with their eating or relationship with food, or has a suspected eating disorder, please contact a regulated health professional or visit http://nedic.ca/

Intermittent fasting (IF) has been promoted as a way to lose weight and improve health markers like blood pressure and cholesterol levels. What is IF? Should you try it?

Restricting energy intake (calories from food and drink) creates a calorie deficit to create conditions that promote weight loss. This is often achieved through daily energy restriction (~500 calories/day). However, some people find this chronic restriction is difficult to maintain. This is where IF comes in. IF is an approach that cycles between periods of limited food or significant calorie restriction, and periods of eating “ad libitum” (as much as desired). It is an ancient practice used by populations around the world.

There are different ways that IF can be approached:

- Alternate day fasting where there is a substantial energy restriction on two to three non-consecutive days per week.

- Modified fasting or Intermittent energy restriction where energy intake is limited to 20-25% of energy needs on scheduled fasting days. For example the 5:2 approach is where energy intake is restricted for 2 non-consecutive days per week and then eating is unrestricted during the other 5 days a week.

- Time-Restricted Feeding (TRF) where food intake is limited to a restricted eating window. So for example, 16:8 means that there is a 16-hour fast, and an 8-hour window in which to consume food). For example, this could mean that you eat between 11am and 7pm. Outside of this 8-hour window, you are fasting.

For more information on IF approaches, read the papers here, here, here and here.

What does the research say?

Research on Intermittent Fasting compared to Daily Energy Restriction

When examining the research on IF, it is important to consider the actual research design. Some aspects to consider include the specific approach to IF used, whether the research involved humans versus animals, how big was the study, how similar you are to the study participants, how long were the study subjects followed, what were the drop-out rates, and whether there was a comparison group.

The results of several studies on humans found that IF did not result in better short-term weight loss (See references 1, 4, 5, 8) or improved health markers like cholesterol and blood pressure (See references 5, 6) compared with daily calorie restriction. What does this mean? You are likely to lose weight with IF, but its effects are no better than daily energy restriction. And compared to “no intervention”, IF promotes weight loss. This is not surprising nor unexpected.

What is different between IF and daily calorie restriction is that some people may find it easier to stick to the IF approach (9). This qualitative study of 13 women who followed a 4-month IF regime found that the IF experience redefined the meaning of dieting and normal eating, and that it was less “cognitively demanding” because the “rules” to follow the IF were easier to understand and follow than those with continuous energy restriction.

This article highlights the importance of finding an approach that matches individual preferences.

What is the mechanism behind Intermittent Fasting?

A mechanism is the biological explanation of how something “works”. Patterns of eating that reduce nighttime eating and extend the nightly fast may result in weight loss and improved “metabolic” health (including blood indicators of the risk of diabetes, cardiovascular disease or cancer).

It is thought that IF improves our metabolic health by impacting our circadian rhythms, our gut microbiome and by changing our modifiable lifestyle behaviours. For more information about these mechanisms, click here and look at Figures 1 & 2. What this latter article highlights is that there is complex physiology happening in our bodies, and that our dietary pattern, including the timing of food intake, can impact this physiology.

What is not clear is whether the weight loss and improvement in metabolic health are the result of the fast itself or whether it is due to the overall negative energy balance that is achieved by any kind of dietary restriction. Or a combination of both. This argument is outlined further here.

Does Intermittent Fasting “work”?

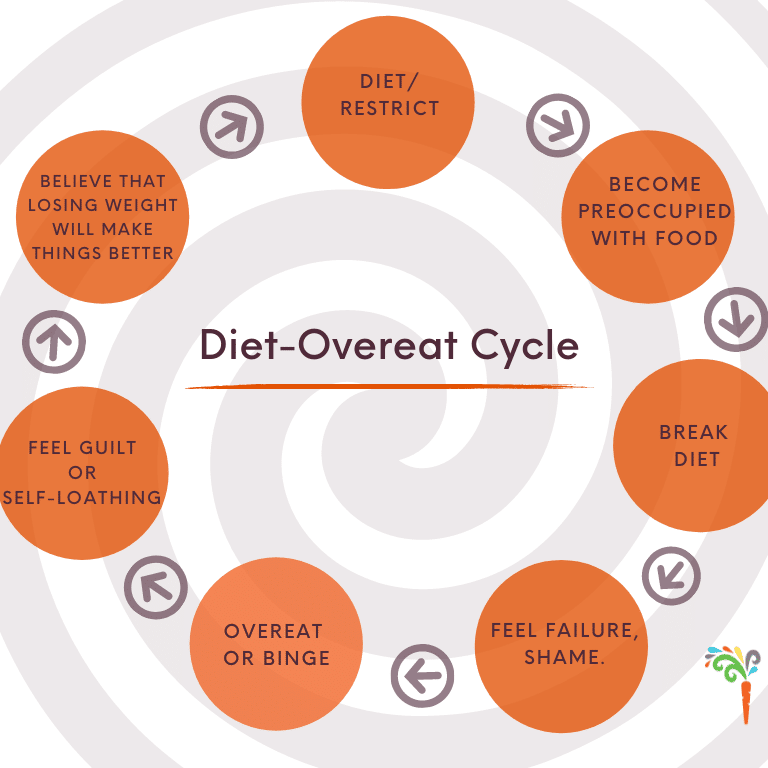

That depends on what you mean by “work”. Will you lose weight with IF? Sure, like any other diet, you are likely to lose weight. That is nothing new. Diets, in the short-term, often result in the weight loss. However, it is well-established that the long-term “results” of diets are abysmal, with most dieters (95%) regaining all the weight they lost, plus more, after two- five years. That plus a slower metabolism. At the moment, there is not enough human research on the long-term effects of IF.

A few observational studies of populations who fast for religious reasons, such as Ramadan or other religious feasts, have noted that weight loss may occur, but that it is also regained. Some markers of metabolic health may also be improved in the short-term.

What are the risks of intermittent fasting?

There are benefits and risks to anything. IF is no different. Some studies have found that some participants report negative side effects like feeling cold, irritable, having low energy or feeling hungry.

What about research drop-out rates? High drop-out rates suggest that whatever intervention is being studied is hard to stick with, and so people drop out. Something can “work”, but if it is really hard to stick with, then does it really work? Drop-out rates were similar or higher in the IF group compared with daily energy restriction, which suggests that the long-term ability for people to stick with IF is just as hard as other diets. And while some authors cite that no adverse effects have been reported, that also depends on what you look for.

Here are some other effects of IF (or other diets) to consider:

- How does IF impact your relationship with food? This is especially important in people with a long history of dieting.

- How do you explain your IF protocol to your family? How does that impact your kid’s learning about what is healthful eating? Kids will watch you, will learn from what you do more so than what you say.

- How does IF impact your body image? How does following IF impact your kid(s)’ thoughts and feelings about their own bodies?

- How does IF support your mental health?

- Does the IF set you up for the diet-binge cycle?

- Does IF make your world bigger (so that you can think and focus on other aspects of life beyond your food intake) or smaller?

When researchers say that no adverse effects have been reported, it can be that the researchers didn’t measure certain variables. What I would like to know is more about the real-life, long-term experience of IF outside of the research protocols and short-term, honeymoon diet-phase hype.

Who should not try Intermittent Fasting?

There is no one-sized-fits-all approach to diet, nutrition and health. There are certain groups who should not try IF:

- people who are on medications for diabetes (unless they are being medically supervised)

- people with a history of eating disorders or disordered eating

- pregnant or breastfeeding women

- children

- IF could be challenging for those working night shifts.

If you want to try IF, check in with your regulated health professional to assess whether this is an approach that is right for you.

Final thoughts on Intermittent Fasting

IF is dieting by another name. While there are scientific explanations by which IF may improve health markers and counteract disease processes in the short-term, we do not know the long-term impact of this approach on people’s physical health, and perhaps more importantly, their mental health.

Everyone is entitled to enjoy a lifestyle that suits themselves. IF is not a one-sized fits all approach. But it may be an approach to consider for some. Any lifestyle intervention comes with pros and cons that should be evaluated against individual values, unique experiences and personal preferences.

For a person to find their best weight, they need to find a way of eating and living that they can enjoy and sustain, so that they can continue to *live* and experience their best life. This exploration requires a person to be committed to the process of change.

The search for this approach within a culture that promotes quick-fixes for health is the holy grail for all of us.

References

For those of you who want to examine the peer-reviewed literature on this subject, here are a few papers to read.

- Headland M1,Clifton PM2, Carter S3, Keogh JB4. Weight-Loss Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Intermittent Energy Restriction Trials Lasting a Minimum of 6 Months. 2016 Jun 8;8(6). pii: E354. doi: 10.3390/nu8060354. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27338458

- Mattson et al, 2017. Impact of intermittent fasting on health and disease processes. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1568163716302513

- Patterson RE1,2,Sears DD1,2,3. Metabolic Effects of Intermittent Fasting. Annu Rev Nutr. 2017 Aug 21;37:371-393. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-071816-064634. Epub 2017 Jul 17. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28715993

- Harris et al. Intermittent fasting interventions for treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports. Feb 2018; 16(2): 507-547. . https://insighovid.com/crossref?an=01938924-201802000-00016

- Trepanowski JF1,Kroeger CM2, Barnosky A1, Klempel MC1, Bhutani S1, Hoddy KK1, Gabel K1, Freels S3, Rigdon J4, Rood J5, Ravussin E5, Varady KA1. Effect of Alternate-Day Fasting on Weight Loss, Weight Maintenance, and Cardioprotection Among Metabolically Healthy Obese Adults: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Jul 1;177(7):930-938. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0936. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28459931

- Seimon et al, 2015. Do intermittent diets provide physiologicl benefits over continuous diets for weight loss? A systematic review of clinical trials. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 418(2): 153-172. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0303720715300800

- Tylka et al. (2014). Review: The Weight-Inclusive versus Weight-Normative Approach to Health: Evaluating the Evidence for Prioritizing Well-Being over Weight Loss. Journal of Obesity. Vol. 2014, Article ID 983495, 18 pages. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/983495.

- Iolanda Cioffi,1Andrea Evangelista,2 Valentina Ponzo,3 Giovannino Ciccone,2 Laura Soldati,4 Lidia Santarpia,1Franco Contaldo,1 Fabrizio Pasanisi,1 Ezio Ghigo,3 and Simona Bo3 Intermittent versus continuous energy restriction on weight loss and cardiometabolic outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Transl Med. 2018; 16: 371. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6304782/

- Donnelly LS1, Shaw RL2, Pegington M1, Armitage CJ3, Evans DG1,4,5, Howell A1,5, Harvie MN1. ‘For me it’s about not feeling like I’m on a diet’: a thematic analysis of women’s experiences of an intermittent energy restricted diet to reduce breast cancer risk. J Hum Nutr Diet.2018 Dec;31(6):773-780. doi: 10.1111/jhn.12571. Epub 2018 Jun 21. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29926996

- Templeman I1,Gonzalez JT1,Thompson D1, Betts JA1. The role of intermittent fasting and meal timing in weight management and metabolic health. Proc Nutr Soc. 2019 Apr 26:1-12. doi: 10.1017/S0029665119000636. [Epub ahead of print]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31023390

Tagged in: Calgary Dietitian, Calgary Nutritionist, fasting, goal setting, Intermittent Fasting, midlife, Over 40, Time-restricted eating, weight loss, weight management

Welcome to the Energize Nutrition blog, where we share evidence-based nutrition content, designed to empower people’s midlife. Take a look around to find information on feeling your best.

If you need more individualized support, reach out to set up a free discovery call with Kristyn Hall.

Battling chronic hunger, poor energy, or inflammation? Discover what this powerful ingredient is and why it might be the solution!